This entry was posted on December 13, 2019.

Colonel Terry Virts (Retired) is a U.S. Air Force pilot and NASA veteran of two spaceflights – a two-week mission onboard the Space Shuttle Endeavour in 2010 and a 200-day flight to the Space Station in 2014-2015. His seven months in space included piloting the Space Shuttle, commanding the International Space Station, three spacewalks, and performing scientific experiments.

While in space he took more than 319,000 photos – the most of any space mission. Virts’ book, View From Above, combines some of his best photography with stories about spaceflight and perspectives about life on Earth and our place in the cosmos. His images are also an integral component of the IMAX film A Beautiful Planet, which Virts helped film and in which he appears.

Submitted by Terry Virts/NASA

I understand you were a photographer before you became an astronaut. How did you get started, and why did it interest you?

As a kid I got a Konica SLR. I had to teach myself exposure, shutter speed, focus, and all that. Basically, I taught myself. Neither of my parents were really photographers, but I just loved it. For some reason I was just naturally inclined towards photography, and my parents supported me by getting the equipment.

Long story short, I kept up with it. I’m that dad whose kids are like, “Dad, quit taking pictures!” I’m always having to stop and take a picture.

How did you join the space program, and how did you end up in the role of ‘space photographer’?

I wanted to be an astronaut since I was a kid. It was just my dream. The first book I read was about Apollo, and I was captured. It’s what I wanted to do, and I had pictures of airplanes and space on my walls. I went through the process of becoming a fighter pilot, a test pilot, and eventually made it into NASA.

Every astronaut has to take pictures. We get formal training, not only for still images but also video. By the time I flew on the space shuttle we had gone entirely digital, and I got designated as the photo/TV guy. I’m a photographer, and I was lucky enough to fly in space, so I guess that makes me a space photographer.

You also had a role in filming the IMAX movie ‘A Beautiful Planet.’ How did that come about?

On my second flight [aboard the ISS] I was a crew medical officer and also a spacewalker, but everybody was a photographer. There was no, “Oh, Terry likes photography, let’s put him up when they’re filming a movie.” Just complete luck of the draw. One day on my calendar before I was in training, it said, “Go to building nine for IMAX training.” I thought, “Hmm, I wonder what it is?” I showed up and the producer and director of photography were there, and I said to myself, “Wow, I get to film an IMAX movie.” There was no thought into it, it just happened.

The right place at the right time?

100% right place, right time. Like we say in the Air Force, I’d rather be lucky than good.

I got to film the movie, and that stuff all went to IMAX, but the stuff I shot for me, that I used in my book, I did as a labour of love. I love photography and wanted to take as many artistic shots as I could.

Most photographers know the drill of throwing gear into a bag before a trip, but space travel obviously requires careful planning. How is the photo gear that goes into space selected?

There are a couple of different ways. There’s NASA equipment, and then there are international partners, like the Japanese and the Europeans, who fly their own equipment. The Russians can get stuff up there really quickly since they don’t have the bureaucracy that we have. They may have less stuff, but if something comes up that they want to fly, they just fly it. NASA has to go through a bureaucratic process and years of approvals.

For example, there’s the GoPro. The Russians wanted to use it, so they built a little box for it and flew a GoPro. I was able to take it outside on a spacewalk and it was really great. We [the US] didn’t have anything for that, and the process of getting it certified would have been expensive and time-consuming. The Russians just built a box and flew it, and it worked. Now I have this amazingly beautiful footage that we never would have had if we had to wait on it.

Can you give us some insight into what types of cameras are used aboard the ISS?

The Nikon D4 was my main camera, and now they have the Nikon D5 professional camera. Then there’s the Canon XF305, which is like a prosumer camcorder, and there are probably 12-15 of those onboard. Each module has one on a bracket. There are another four or five XF305s just velcroid to the wall so that if you need to film something fun or do an experiment, you can do that.

We also had a camera called a Ghost, which is similar to a GoPro. You could plug it in via HDMI and have it downlinked in real-time to show the ground what you were doing. You could squeeze it into tight places. When three Ghosts showed up, I thought “Cool!” so I kept one for myself and another astronaut wanted one. Literally the next day, the other person lost it. We went months with only two Ghosts and finally, at the end of my mission, I’m thinking, “All right, I’ll call the ground and fess up. Hey Houston, sorry, we can’t find one of the Ghosts.” That afternoon we found it. It had floated underneath a work table and was probably there for months.

We also had a Panasonic 3D camcorder you could use to film in 3D. I bought myself a 3D TV and tried to film stuff, then nothing happened with it. I don’t even know if NASA ever processed the 3D stuff. I was kind of disappointed about that.

I imagine you also had some cameras for shooting the IMAX film.

We had a Canon 1DC and C500. The 1DC is a professional camera and the C500 is a Hollywood video camera. Those were used for the IMAX.

We also had a Red Dragon, which at the time was the first ever ultra-high-def 4K, Hollywood quality video camera. That thing was just awesome. They warned us and warned us that the file size was too big, so nobody used this thing, and towards the end of the mission I decided, “Man, I took all these stills, I want to get the Red out.” I started filming exclusively with the Red for my last week and shot around a terabyte of video. Houston just about died. It took them a week to download it. It was beautiful.

I was doing a video Skype with [Hollywood director] James Cameron from space, and my crewmate was showing him around and said, “Hey, here’s my crewmate Terry Virts, playing with cameras like he normally is.” I had the Red Dragon, and James looked at it and said, “Oh, I filmed Avatar with that camera.” That was pretty cool.

DATE: 6-26-14

LOCATION: Bldg 9NW

SUBJECT: Expedition 42/43 crew members Samantha Cristoforetti (ESA) and Terry Virts (NASA) performing IMAX C-500 cinematography training with instructors James Neihouse and Toni Myers.

PHOTOGRAPHER: Lauren Harnett

Do you run into any special equipment challenges in space?

The big issue you have in space is radiation, and your chips get damaged from radiation. If you ever look at a NASA video and see a bunch of white, blue or green specks that don’t move on a black field they’re radiation-damaged pixels. If they’re moving, they’re stars. Before every IMAX shot, you’re supposed to take a black field image. That would give them data for where the bad pixels were, and they could remove them.

We would get dust on the chip, but that would only happen after about 100,000 pictures. Basically, we would start seeing that as the shutter went up and down, some of the metal would shave off, so there would be little flecks of metal from the shutter.

What about lighting?

Lighting inside is not that big a deal; the internal lighting is not that bad. The problem is, if something was inside and you wanted the Earth exposed at the same time, the camera would need a flash.

I started filming exclusively with the Red for my last week and shot around a terabyte of video. Houston just about died. It took them a week to download it.

But for video, you don’t have the equivalent of a flash. We had still lights, but there weren’t enough lumens on them. There was one particular scene in ‘A Beautiful Planet’ when Samantha [Italian astronaut Samantha Cristoforetti] was in the cupola taking pictures, and I was floating towards her, and the white clouds were too bright and just blew out the Earth. In order to get a picture with both the person inside and the Earth properly exposed, we had to be over a jungle because that would be dark green. We waited until we were going over the Amazon, which is white normally, but Samantha was looking and she’s like “All right, here comes a big patch!”

I started shooting, and then I pushed off. I slowly started moving in towards her, and she was pretending like she was taking pictures. IMAX wanted 30 seconds clips, that was about the standard scene length, and literally at 31 seconds, boom! The background turned into white. It was like a perfectly well-timed shot.

When shooting on a spacewalk, I’m assuming you don’t just put the viewfinder to your eye and shoot.

Actually, you do! When I was doing my spacewalks it [the camera for spacewalks] was a Nikon D2. You can lift the viewfinder to your face and aim it wherever you want, though I never did. I just pointed it in the right direction. You don’t put a 100mm lens on it, but something like a 24mm. It doesn’t have to be perfectly framed.

I took over 300,000 photos in space, but on each of my three space walks I took about ten. That just goes to show you how busy I was.

I took over 300,000 photos in space, but on each of my three spacewalks, I took about ten. That just goes to show you how busy I was. I felt like I was on the clock, so I didn’t have five seconds to stop and take a picture. Plus, the guy I was outside with is one of those people who’s not a photographer, thinks taking pictures is wasting time, and wanted to keep on moving. I just never had time to stop and take the pictures I wanted to take. The problem with taking pictures outside is the time crunch.

What’s your artistic approach to shooting in space?

A lot of guys get the zoom lens out. They zoom in on cities at night, and I did some of that, but you can fly over a city and take a picture from an airplane and it looks exactly like the zoom lens from space. My favourite kind of shots were more big picture; Earth and space, and wide angle, rather than the zoom-in. I wanted to get pictures that you couldn’t get from an airplane.

Most photographers can tell you at least one story about a great shot that got away. Did you experience that?

One day I let go of my CF card by accident. It floated and I was like, “No!” as I reached for it. It floated right between two racks. There’s got to be a two-millimeter gap between racks, and it literally went right down there and I never saw it again. It was a beautiful night aurora scene. I’m still mad about it, but the other 320,000 pictures I took came out fine.

What subjects did you enjoy photographing the most?

Sunrises and sunsets were my favorite thing. It was probably day 195 out of 200, and Samantha sees me taking another time-lapse of a sunset and says, “Terry, haven’t you taken enough sunsets?” I said, “I still haven’t gotten the perfect one. I just need one more…”

The photographer’s curse.

Yes, the perfect shot. Or moonset, right? Moonrise and moonsets were awesome. Those pictures are just amazing. In a good sunset or sunrise, you can see so many details in the clouds. The chip doesn’t capture it like the eye does, but it’s pretty close. I love those pictures.

So, did you ever get the perfect sunset?

The very last picture I took in space – I was coming back to Earth in a couple of hours – I wanted to get one more picture. I went down to the Cupola and took off what’s called a scratch pane, which is this piece of plastic that’s supposed to protect the window but all it does is ruin pictures. Whenever you see a sun shot with flared smudge marks it’s just the scratch pane. I closed the aperture to F22 to get a starburst effect, took a picture and looked at it, and I remember thinking as I looked at it on the screen, “That’s the best picture I’ve ever taken in my life. I’m done.” I pulled the CF card out, downlinked it, put my space suit on and came back to Earth. That was the peak of my photography career, it will never get better than that.

Did you take any photos that had an immediate impact back on Earth?

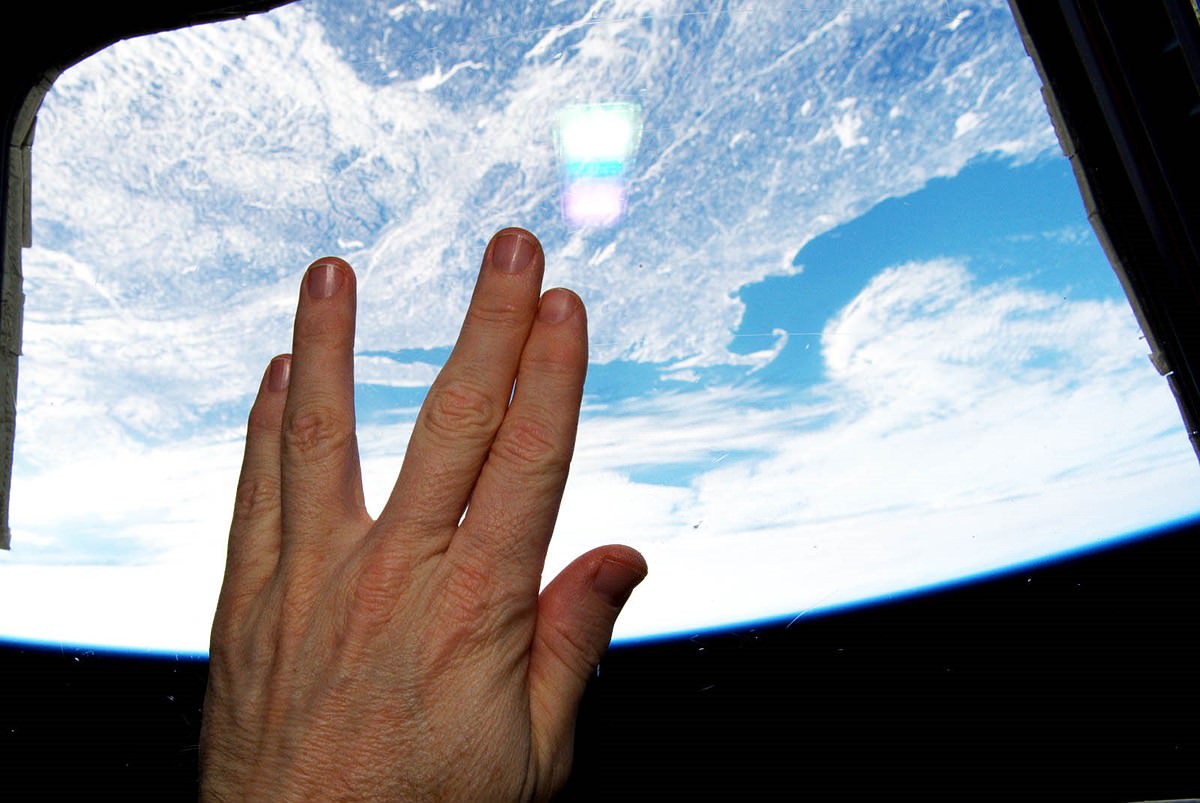

The most impactful one was the Spock picture. The day before my third spacewalk I get an email, “Hey, Leonard Nimoy passed away. Can you do something?” I’m thinking, “I don’t have any time, I don’t know what I’m supposed to do.” I ran down to the Cupola and tried to get one of those pictures where my Vulcan salute was properly exposed along with the Earth being properly exposed, but you need to have the right flash and a closed [small] aperture for more depth of field.

I had to get all that stuff set up, fiddled around, probably took 10 or 20 pictures, and finally got one that looked OK. I tweeted it and it got huge instantly – I don’t know how many tens of thousands of likes. It got millions of views. When I travel around the world, people know that tweet. They don’t know it’s me. It wasn’t about me. I just tweeted a picture, and there was no doubt in anybody’s mind what I meant. It was a really cool way to have a tribute to Mr. Spock. What I didn’t know was that in the background was Boston, Leonard Nimoy’s hometown. Like I said, I’d rather be lucky than good.

I've been learning to photograph the Aurora borealis, but I’m used to doing it from below. What’s it like to photograph the Aurora from above?

One night I was in the Cupola, hoping for a southern aurora. You never know what you’re going to get; it depends on the sun activity and how close your orbit is to the magnetic pole. I saw this big, giant green cloud. I mean, it was huge. It was way bigger than any I’d ever seen before, and it was right in our orbital path.

There I was floating, and we flew right through this aurora. Above, below, and to both sides, we were surrounded by green plasma. It was like I was in a J.J. Abrams Star Trek movie when they fly through a nebula. It was totally like that, except that I was floating and it was real, but there were no Klingons, so I was good. But that was the most surreal aurora experience. You could see it moving with your eyes, in real time you could see the waves shimmering. Even though the camera brings the colours out more than your eyes see, my eyes, anyway, saw those colours – a little dimmer and less vibrant, but they were there.

Do you feel that your unique opportunity to work in space gives you any special responsibility as a photographer?

I do. One night we were having dinner in the Russian segment, and the Russians have this beautiful window, and it was open and you could look down and see the Earth go by. I said, “Look at that guys! There are over six billion people down there and only six of us up here.” We’re one in a billion, that’s how lucky we are.

It put our fortune, and luck, in context. I feel a duty to share the story. Not only the adventure of space flight but for me, it was more about life on Earth. Space flight is interesting, and fun, and exciting, but the bigger, deeper lessons learned were about the people, and how to treat each other, and life on Earth. I definitely felt a responsibility, and privilege, to share things.

Has your experience as a space photographer had any impact on the way you photograph back on Earth?

I always look up. Most people spend their lives looking down at the ground, and I try to look up. To see clouds, to see the sun’s reflection through the atmosphere, rays of sun peeking through clouds, to see the colour of blue in the sky, to see birds, or when you’re in a city, you see architectural patterns. I always try to look up, and maybe in some small way, I think of space when I look up.